For decades, I felt this overriding sense of doom whenever I thought my writing wasn’t going well. The doom feeling would squat like a barrier between me and everything else in my life until I’d fixed the writing problem. It didn’t matter what else was happening. Date nights. Tropical holidays. Christmas mornings. Whatever enjoyment I’d normally have experienced would be squashed by the weight of The Doom.

It took me a long time to focus on The Doom as something specific arising from the writing process—to pick it out of the general noise of negative emotions that I was carrying most of the time. But as I felt better and better in my daily life, that changed.

And then, couple of years ago, I was sitting on my local beach with a mystery novel on a gorgeous day, and thoroughly failing to enjoy myself. I’d been looking forward to this afternoon off, but I just felt grim and out of sorts. It wasn’t the worst Doom I’d experienced by a long shot, but it still felt like it was blocking the sun. I had left an article at a sticky point that morning when I called it quits for the day, and the Doom was the consequence.

But at this point, I was too used to feeling good to just accept The Doom as simply the cost of doing writing business. Its weight on my chest now really stood out non-optimal. And, for the very first time, it also stood out as weird. I had written a PhD dissertation and two books. I’d written countless articles and newsletters and posts. I’d been amassing evidence that I’m a good writer since I was about seven years old. Why the hell was I so worried about fixing a fucking blog post? Yeah, I’d left the writing at a problem point, but why couldn’t I trust that I’d solve the problem? Why was I condemned to feel The Doom until I’d proved myself capable for the trillionth time?

To find out, I used the same process I do in my coaching to locate the underlying rule that had tethered writing to this intense experience of dread. It turned out my brain had stored a prediction in implicit memory that said writing HAD to work for me, every single time—or else I might as well be dead (!!). When this rule got activated by something going wrong in a chapter or article or 500-word blog post, my brain responded as if my actual physical survival were under threat. It flooded me with negative emotions and fight-or-flight chemicals, which was what I experienced as The Doom.

No wonder it felt like The Doom obliterated everything else. Trying to enjoy a beach day pumped full of those chemicals was like trying to experience a nice stroll while being chased by a bear.

Eventually I changed those implicit memories via memory reconsolidation, which got rid of The Doom for good. I still prefer to end a writing day on a high point if I can, just because it feels nice. But if I can’t, it’s not a big deal. I know I’ll fix it eventually. I can trust that, because the stakes are no longer so high that the smallest smidgen of doubt feels like a mortal danger. I actually get to enjoy the beach days and road trips and whatever else, even if whatever I’m working on isn’t working yet.

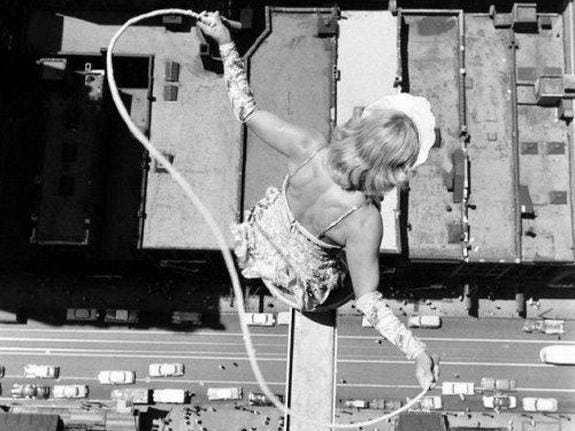

It’s like I’d been walking a tightrope over an abyss forever, and I finally have a net. Even if I fall, I know I’ll perfectly safe. In fact, I’ll bounce right back up, unscathed. It feels so sumptuous and rich to write this way. I don’t think I ever really understood that it could feel like this, until it happened to me.

That made me curious about how common this experience actually is. So I checked in with a colleague who is super productive. He’s not some soulless, go-getter machine; he’s just loves his academic research and seems to have zero resistance to doing it. I wondered if what I was feeling now was anything like the way writing is for him.

So I asked him how he felt when he had to leave an article or chapter at a point where something felt broken and he didn’t know how to fix it. He said, Oh, I mean, it’s fine. I know I’ve solved problems like that so many times in the past. Why wouldn’t I solve it this time too?

Good fucking question, Super-Productive Guy.

In some ways, talking to him solidified my sense that some lucky people are just born into this different reality, where using their talents isn’t an uphill battle fraught with angst and terror. I mean, my colleague had just been out there living Doom-free the whole time.

In the end, though, my take away is something like the opposite. There isn’t some essential, in-born distinction between those who encounter The Doom and those of us who don’t. I crossed over to the Doom-free side, and it’s literally my job to help other people get there too. And it’s not even that hard to get there, once you have a guide who knows the way. It’s definitely way, way easier than dealing with The Doom for years on end.

I also think that the luck is more evenly distributed across these different camps than it may seem at first glance, too.

Here’s why. When you deal with what feels like an existential risk on a daily basis, you wind up building traits that people like Super-Productive Guy may not have had to develop. You can’t inch your way across a deadly abyss day after day without honing your grit and courage. And you can’t do it shlepping the weight of The Doom on your back without developing serious determination and endurance.

Facing down what your brain tells you is a mortal risk, routinely, is badass. The risk may be only in your head, but when it comes down to it that’s where we experience every risk, even a real-life bear. And that means that when you try to use your talents, you’re living at a pitch that is heroic, even if it also feels miserable at the moment.

I’m not saying any of us would choose to teeter over the abyss. Dear God, am I not saying that. I’m saying that having to brave the abyss makes us powerful, in ways that are hard to see when you’re still just focused making it across. But just imagine what you’ll be able to do with all that power, once you can finally see the net.